The last weeks I have been settling in a new home. That is when you suddenly become aware of the routines that make up daily life, and have to recreate them in slightly differently ways. The light switch can’t suddenly be found in the dark, you can’t recognise individual noises, things need new places, new formations. New ways of doing become small rituals of inhabiting, small meditative actions, before disappearing again from your consciousness, as they once again become routines, the kind of everyday life, that is hardly noticed.

This has been on my mind thanks to Kirsi Saarikangas and her not at all new book “Eletyt tilat ja sukupuoli” (SKS 2006), where she investigates the boundaries between spaces and inhabitants, repeatingly emphasizing how architecture is constantly co-created by the people in a space, by their actions and reactions. Architecture encourages some behaviours more than others, but is also constantly re-interpreted and changed by its users. In her book this comes of course more elegantly put and with a hearty dose of Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty and Beauvoir.

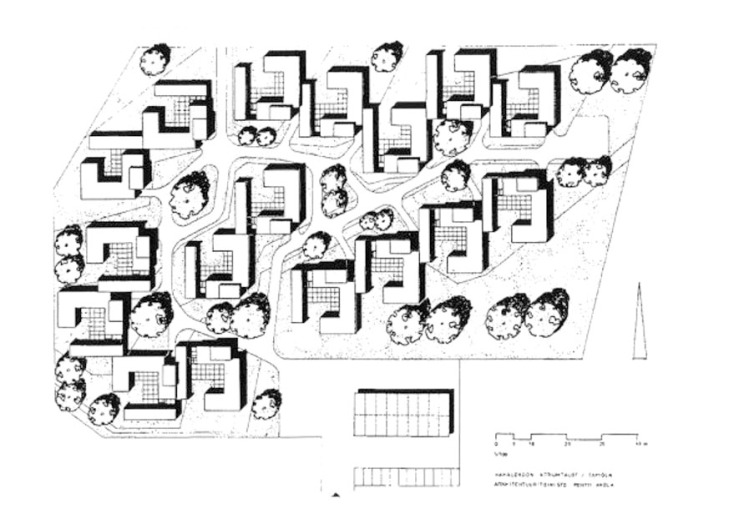

Taking these thoughts to the 1970’s suburb of Olari in Espoo allows trying new perspectives. Olari can of course be looked at as belonging to a larger shift in society in the 1970’s, from rural to urban, to new jobs in the city, to new industrially built homes for everyone. It is also possible to view it as an experimental project by an eccentric building contractor Arvi Arjatsalo and two young and ambitious architects, Simo Järvinen and Eero Valjakka, and as their pragmatic work of art.

But Olari is now something beyond what the politicians, city planners, builders and architects had in mind. For almost 50 years it has been a home for thousands of people hating and loving it. As the built environment might have changed their life, the inhabitants have left their own traces there, sometimes adapting, sometimes resisting change. For my book I visited homes in Olari that had virtually not changed in decades, looking like it was still 1972. Some homes had little resemblance to the world outside, living in their own time. New, overlapping, contradicting, personal layers of meaning have been added to the place and the buildings. People who spent their own childhood there come back with a feeling of nostalgia that was unthinkable a few decades ago.

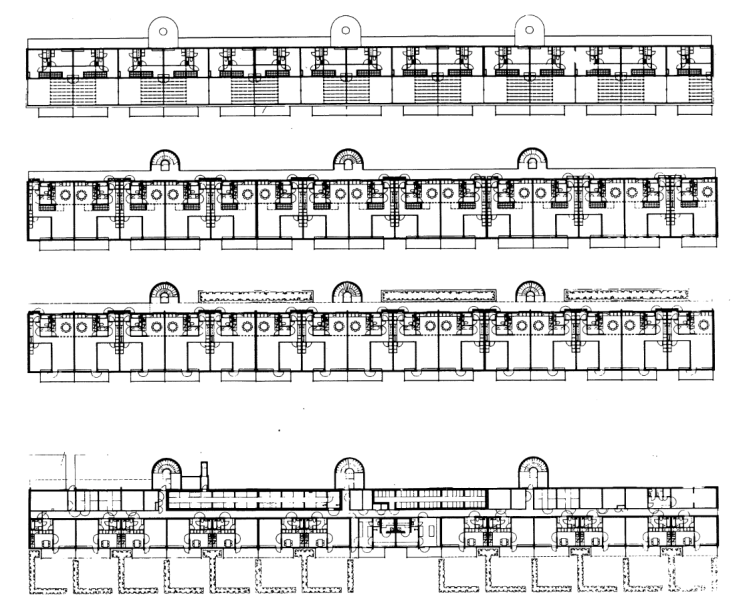

On a practical level Olari homes have adapted remarkably well to completely new ways of living, thanks to the constructive system that was ahead of its time and already prepared for change. Instead of standard bearing walls there are bearing columns that allow a free flow of spaces and lots of individual changes. Freedom on the inside was contrasted with systematic repetition, even monotony on the outside, that was slightly softened by the ever-present forest surrounding the houses.

And the sauna. Olari was the first Finnish building project to implement individual saunas inside the apartments. The sauna space even had direct access to the balconies. The sauna was a technical novelty that in an unprecedented way managed to give new city dwellers a new sense of luxury as well as a sense of autonomy and emotional ownership. Standing in the bath towel on your balcony, drinking beer and watching the sunset. Now that’s being-in-the-world if anything, right Heidegger?